Cats

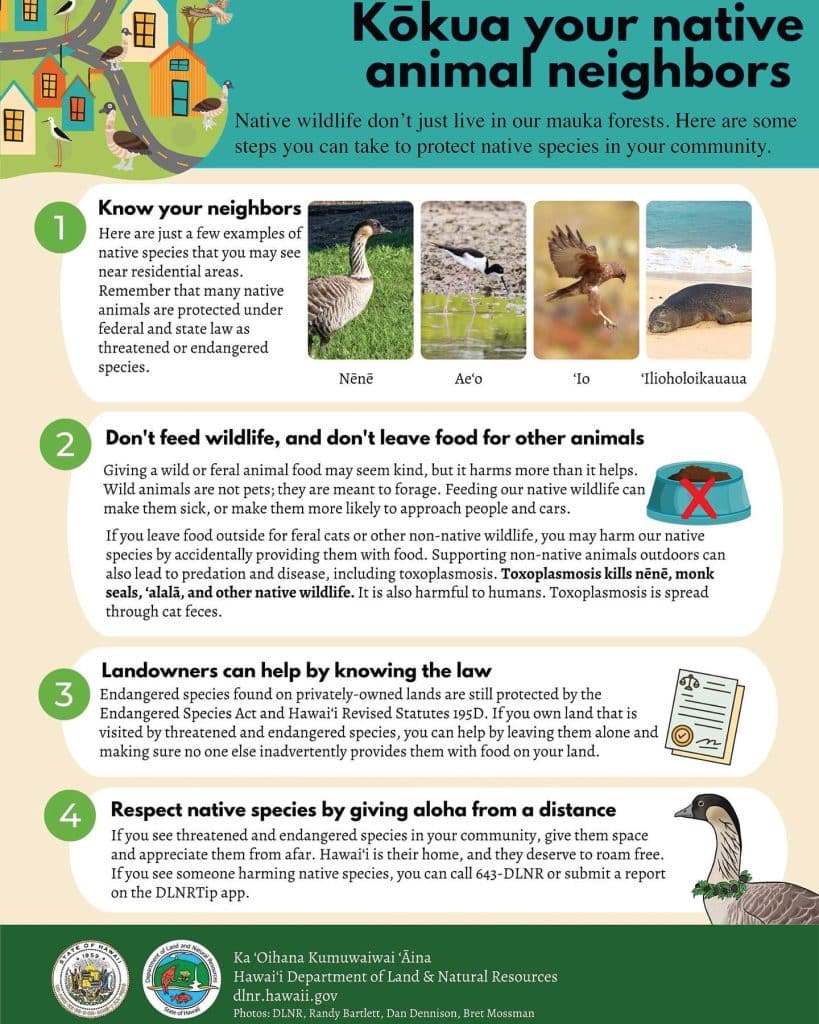

Cats in Hawaiʻi pose a major threat to native wildlife, including Nēnē, through direct predation, habitat displacement and the spread of disease and parasites like Toxoplasma gondii. You can help by reporting feral cat colonies and cat feeding by using our CatMap tool. We also started a petition to address county rules related to pet abandonment – cited by cat colony managers as one of the major issues that prohibits adequate management.

Habitat Displacement

Feral cat colonies and community feeding can have significant impacts on Nēnē and other native species. Over the past few years we have documented Nēnē eating cat food, habituating them to dangerous areas like parking lots. Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources have issued this flyer to educate visitors and residents about the risks of feral cats on native species.

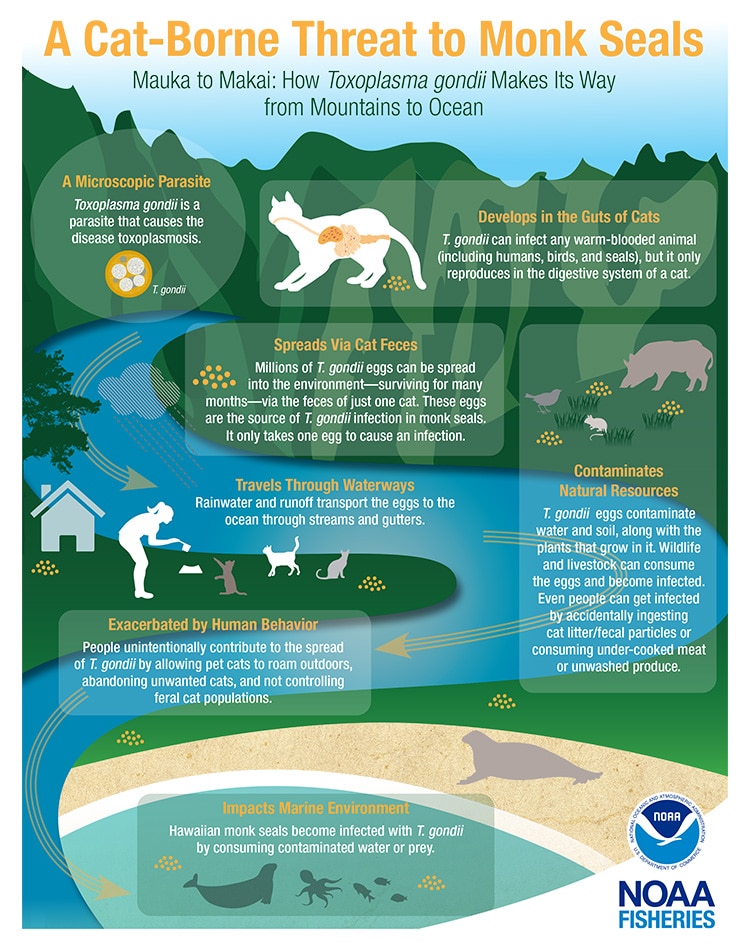

What is Toxoplasma gondii?

Toxoplasma gondii, a parasitic organism primarily infecting cats, causes toxoplasmosis, which has significantly impacted various wildlife species in Hawai’i. This disease has been the documented cause of death for several native species including Nēnē, Hawaiian monk seals, false killer whales, spinner dolphins, ʻAlae keʻokeʻo, ʻAlalā, red-footed boobies, and Koloa.

Cats shed the parasite’s resilient oocysts in their feces, which can contaminate water sources. After 1-5 days in the environment, these oocysts sporulate and become infective. Understanding and addressing this issue is crucial for safeguarding the delicate ecosystems in Hawaiʻi and its unique, indigenous species, as domestic cats are the only known definitive hosts for T. gondii in Hawaiʻi.

Why is T. gondii bad?

Toxoplasma gondii poses a significant threat in the Hawaiian Islands, which has the highest per capita number of endangered species in the USA.

Toxoplasmosis has been linked to the deaths of the following Hawaiian species:

- Spinner dolphins

- Hawaiian monk seals

- False killer whales

- ‘Alae ke‘oke‘o

- ʻAlalā

- Nēnē

- Red-footed booby

- Koloa

Toxoplasmosis is documented as the most significant cause of death in Hawaiian monk seals in Hawaii (Barbieri et al. 2016).Researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi found that T. gondii caused the deaths of two spinner dolphins, highlighting its lethal impact on diverse wildlife. Similarly, a study in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases indicated that infectious disease is the third most common cause of death with Toxoplasmosis being the chief culprit.

T. gondii’s influence extends beyond its immediate lethal effects. It can alter the behavior of infected animals, increasing their vulnerability to dangers like predators or vehicles. For example, infected rodents display less fear of cats, boosting their predation risk. This behavior change benefits the parasite, as it requires cats for its life cycle. The widespread presence of T. gondii, its ability to infect various animals, and its environmental resilience pose a continuous threat to both animal and human health. Infection with toxoplasmosis during pregnancy can lead to serious health risks for the baby, including blindness, mental disability, or severe eye and brain damage at birth, especially if the mother contracts the infection shortly before or during pregnancy.

What you can do to help

- Submit feral cat sightings using our CatMap Tool!

- Keep Cats Indoors: Extends their lifespan, protects local birds from predation, and significantly reduces the spread of toxoplasmosis.

- Spay and Neuter Your Cats: Helps prevent the birth of more kittens, indirectly reducing the spread of T. gondii, though it doesn’t stop cats from getting or transmitting the parasite.

- Abide by Local Laws: In Hawaii, abandoning cats or kittens outdoors or at feral cat colonies is illegal; unwanted animals should be taken to shelters for potential adoption.

- Do Not Feed Feral Cats: Discourages the growth of feral cat colonies, reducing abandonment and the spread of T. gondii eggs into the environment.

References

Dobson, A. P., Bradshaw, A. D., & Baker, A. J. M. (1997). Hopes for the future: Restoration ecology and conservation biology. Retrieved from http://www.lerf.esalq.usp.br/divulgacao/recomendados/artigos/dobson1997.pdf

Berdoy, M., Webster, J. P., & Macdonald, D. W. (2000). Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 267(1452), 1591-1594. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2000.1182

Vyas, A., Kim, S.-K., Giacomini, N., Boothroyd, J. C., & Sapolsky, R. M. (2007). Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(15), 6442-6447. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608310104

Poirotte, C., Kappeler, P. M., Ngoubangoye, B., Bourgeois, S., Moussodji, M., & Charpentier, M. J. E. (2016). Morbid attraction to leopard urine in Toxoplasma-infected chimpanzees. Current Biology, 26(3), R98-R99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.020

Work, T. M., Verma, S. K., Su, C., Medeiros, J., Kaiakapu, T., Kwok, O. C., & Dubey, J. P. (2016). Toxoplasma gondii antibody prevalence and two new genotypes of the parasite in endangered Hawaiian Geese (Nene: Branta sandvicensis). Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 52(2), 253-257. https://doi.org/10.7589/2015-05-130

Scallan, E., Griffin, P. M., Angulo, F. J., Tauxe, R. V., & Hoekstra, R. M. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–unspecified agents. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 16-22. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1701.091101p2

Gao, X., Wang, H., Wang, H., Qin, H., & Xiao, J. (2016). Land use and soil contamination with Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in urban areas. Science of The Total Environment, 568, 1086-1091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.165

Gajewski, P. D., Falkenstein, M., Hengstler, J. G., & Golka, K. (2014). Toxoplasma gondii impairs memory in infected seniors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 36, 193-199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2013.11.019

Beste, C., Getzmann, S., Gajewski, P. D., Golka, K., & Falkenstein, M. (2014). Latent Toxoplasma gondii infection leads to deficits in goal-directed behavior in healthy elderly. Neurobiology of Aging, 35(5), 1037-1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.012

Arling, T. A., Yolken, R. H., Lapidus, M., Langenberg, P., Dickerson, F. B., Zimmerman, S. A., … & Postolache, T. T. (2009). Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(12), 905-908. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c29a23

Flegr, J., Prandota, J., Sovičková, M., & Israili, Z. H. (2014). Toxoplasmosis – A Global Threat. Correlation of Latent Toxoplasmosis with Specific Disease Burden in a Set of 88 Countries. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e90203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090203

Torrey, E. F., & Yolken, R. H. (2003). Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 9(11), 1375-1380. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0911.030143

Yolken, R. H., Dickerson, F. B., & Torrey, E. F. (2009). Toxoplasma and schizophrenia. Parasite Immunology, 31(11), 706-715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01131.x

McAuley, J., Boyer, K. M., Patel, D., Mets, M., Swisher, C., Roizen, N., Wolters, C., Stein, L., Stein, M., Schey, W., et al. (1994). Early and longitudinal evaluations of treated infants and children and untreated historical patients with congenital toxoplasmosis: the Chicago Collaborative Treatment Trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 18(1), 38-72. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.1.38. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis 1994 Oct;19(4):820. PMID: 8054436. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8054436/

Wallon, M., & Peyron, F. (2018). Congenital Toxoplasmosis: A Plea for a Neglected Disease. Pathogens, 7(1), 25. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010025. PMID: 29473896; PMCID: PMC5874751. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5874751/

Markell EK (1986) Other Blood-and Tissue-Dwelling Protozoa in: Medical Parasitology, 6th Edition. WB Saunders Co: 131-138.

McLeod, R., Lykins, J., Noble, A. G., Rabiah, P., Swisher, C. N., Heydemann, P. T., … & Withers, S. (2014). Management of congenital toxoplasmosis. Current pediatrics reports, 2(3), 166-194. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40124-014-0055-7