Na Nēnē o Kaua‘i

By Wendy Feltham

02/28/2023

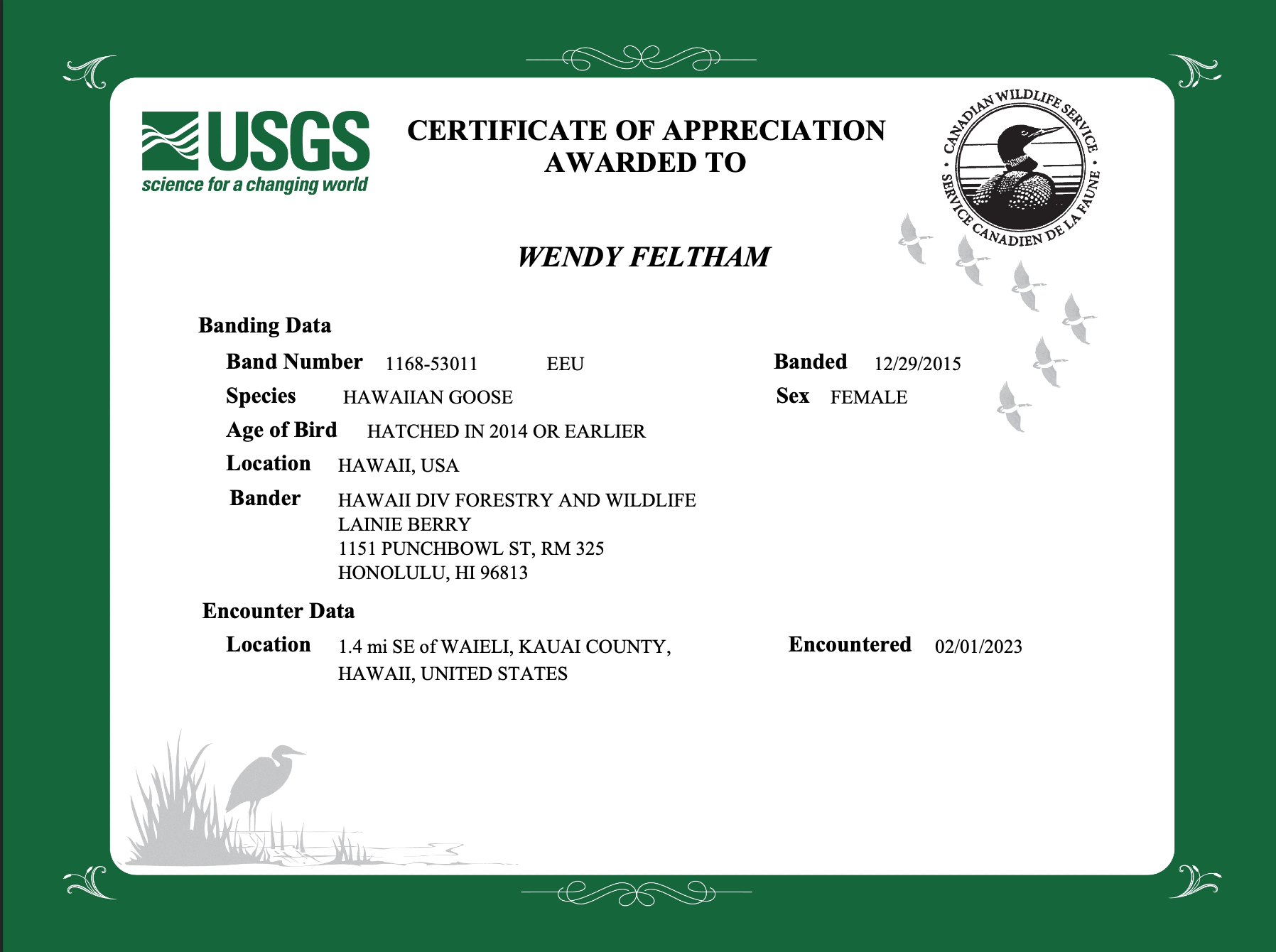

Setting out on a two-week vacation in Kaua`i, I never imagined I’d collect almost 40 Certificates of Appreciation from the U.S. Geological Survey for reporting banded Nēnē. I had seen Nēnē on previous trips to Kaua`i, noting them as a “Life Bird” for me in the year 2000, but this time I watched them closely and observed their fascinating behavior, finding them in diverse surroundings, from wildlife refuges to industrial settings.

Southwest Shore

Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary

Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary

It all started when my husband and I rented a cottage in Waimea. Driving north along Kaua`i’s Highway 50, we spotted our first “Nēnē Crossing” sign near a wetland. We pulled into an unmarked gravel parking lot, and were surprised to find a sign announcing Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary. And there was a Nēnē, with a blue band on the right leg, YXU. Having reported Banded brant in Washington state, I knew to photograph the band and to note which leg wore it.

The 35-acre Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary is a former sand mine that has been converted to a set of managed ponds. It’s part of a restoration project planned to cover 135 acres and is filled with native plants. We were excited to find more endemic birds, including Hawaiian stilts, Hawaiian coots,

Driving back to our cottage, we noticed a flock of Nēnē foraging on both sides of a nearby gate marked “No Trespassing.” There were no people in this industrial setting, but someone had erected a “Nene X-ing” sign. I aimed my zoom lens through the chain link fence to photograph about a dozen banded Nēnē, including two families with immature Nēnē.

It’s fun to watch Nēnē as parents, as they carefully protect and encourage their juvenile offspring.

That night I completed USGS’s online form to report a banded bird at https://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/bblretrv/ and posted photos of each Nēnē on iNaturalist, where I post “observations” of plants and animals almost every day. That’s how I met Jordan, founder of nene.org and the iNaturalist project, “Banded Nēnē in Hawaii,” which both track banded Nēnē.

North Shore

Makai Golf Course

Following a six-hour thunderstorm, my husband and I headed to our next rental cottage in Hanalei, on the north side of Kaua`i. The small bridge over the Hanalei River was flooded, so we spent the afternoon in Princeville, a community of condominiums with a huge golf course. I was delighted to find dozens of Nēnē sprinkled across the vast lawns of Makai Golf Course, still safe after the ferocious storm. Some were banded, and this is where I first observed a Nēnē flapping its wings, seemingly for the pure joy of it! I watched families with adorable fuzzy juveniles, with a few youngsters venturing out on the golf course without parental supervision.

The golfers didn’t seem to notice the magnificent geese and endemic birds around them. I learned online that the Makai Golf Course is a birding hotspot! Along with the endemic birds, a rare Snow goose (who had somehow arrived from Alaska) rested near two Nēnē, a Black-crowned night heron fished in the rather polluted-looking pond, and a Western meadowlark sang from a tree. I watched a Nēnē family enter a pond for a swim, and later read in my 1989 edition of the field guide, The Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific: the Nēnē “inhabits rocky, sparsely vegetated, high volcanic slopes. Not usually observed near water, but will swim if a body of water such as a ranch pond is available.” This golf course is a long way from volcanic slopes!

Kīlauea Point Lighthouse

The storm passed, we settled into our Hanalei cottage, and set out to explore the most special settings for Nēnē of all. Having traveled many times to Kaua`i over the years, we knew we wanted to spend part of a day at the Kīlauea Lighthouse. In efforts to control the recent surge in tourism, advance reservations are now required, and only for a 45-minute visit. That wasn’t enough time to fully appreciate the soaring Laysan albatrosses, the Red-tailed and White-tailed tropicbirds, or the nesting Red-footed boobies, but we did encounter more banded Nēnē. One padded through the parking lot wearing a tattered red band, the only red one I ever saw, but with only a partial band legible, I never learned who NP was.

Some of the lighthouse Nēnē are accustomed to people, and forage right on the lawn as tourists take selfies with them. We watched three Nēnē, as CEZ chased 510, and then 528 and 510 flew off. My certificates later told me that 528 was a female, 510 was a male, and they were both born in 2011 or earlier, banded the same day, March 29, 2012. The male chaser, CEZ, was born and banded three years later. Since Nēnē can stay in pair formations for life, 510 may not have liked CEZ’s behavior!

We visited the lighthouse a second time, but without a reservation we knew we could only could only watch the seabirds from the overlook. Driving a mile from the town of Kīlauea, we were delighted to discover a dozen Nēnē right beside the road. A family of two banded adults and two fluffy juveniles posed for me.

Hanalei Taro Fields

One sunny morning I wandered from bustling downtown Hanalei to the peaceful adjacent Taro fields with views of waterfalls that originate on Mt. Wai`ale`ale, one of “the wettest spots on Earth.” In awe of the views and sounds around me, I watched 12 adult Nēnē forage in a flooded field filled with non-native Bluemink flowers. Many bird species have been introduced to Hawaii from Asia, Central and South America, and elsewhere. I listened to Common mynas chattering loudly, and Red junglefowl (feral chickens and roosters) serenading. I watched Red-crested cardinals perch briefly on the Taro plants, while Zebra doves nibbled on grass, and a White-rumped shama sat on a fence. Monarch butterflies fluttered past.

After standing still for half an hour, entranced by my surroundings, I glimpsed three Nēnē walk by wearing bands. One didn’t wear the typical blue band with white lettering, but orange with black letters: AAH. This Nēnē was exactly a year old, banded on 2/8/22 when she was too young to fly. Later I wrote to ask Jordan how long Nēnē live. He replied, “The median age of the current population in our catalog that has been seen at least once in the previous 5 years (n= 787) is 3.88. For sightings in all years (n=1577) the median age = 3.12. The current longevity record is 23.8 years.”

Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge

One overcast day, my husband and I drove our rental car into the Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), as far as the `Ōkolehao Trailhead, where we parked, planning to hike. I headed out first, then huddled under a tree in the downpour, texting my husband just a few yards away in the car. The rain cleared, and driving back we pulled off the road a few times to watch birds with our binoculars.

Hanalei NWR is one of three refuges within the Kaua`i NWR Complex, providing one of the most important wetland habitat sites in Hawaii for the recovery of the endangered endemic species.

Nēnē are descendants of Canada goose ancestors, which arrived in Hawaii about 500,000 years ago. Hunting and destruction of the environment by European settlers decimated the Nēnē population. From 1960 to 1997, captive-reared Nene introduced to Maui and the Big Island didn’t fare well, given the prevalence of the mongoose, a non-native predator.

From 1991 to 2000, captive-reared Nene were released in the Hanalei NWR.

Happily, Kaua`i has no mongoose population. Nēnē are considered a conservation success story there, and the US Fish & Wildlife website states, “The 2022 annual nēnē population survey estimated 3,862 statewide with 2,430 of those birds on Kaua’i.” We were fortunate to observe families of Nēnē thriving in this pristine and spectacular valley where Hawaiian farmers have cultivated Taro for a thousand years. May Nēnē continue to thrive in this valley over the next thousand years!

About the Author

Wendy Feltham is a photographer and citizen scientist who lives on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state. She wrote about Banded brant for the Rainshadow Journal: https://rainshadownorthwest.com/2022/04/10/beautiful-banded-brant/

Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary

Kawai`ele Waterbird Sanctuary